At a fundamental level it’s important to understand how JavaScript timers work. Often times they behave unintuitively because of the single thread which they are in. Let’s start by examining the three functions to which we have access that can construct and manipulate timers.

var id = setTimeout(fn, delay); – Initiates a single timer which will call the specified function after the delay. The function returns a unique ID with which the timer can be canceled at a later time.var id = setInterval(fn, delay); – Similar to setTimeout but continually calls the function (with a delay every time) until it is canceled.clearInterval(id);, clearTimeout(id); – Accepts a timer ID (returned by either of the aforementioned functions) and stops the timer callback from occurring.

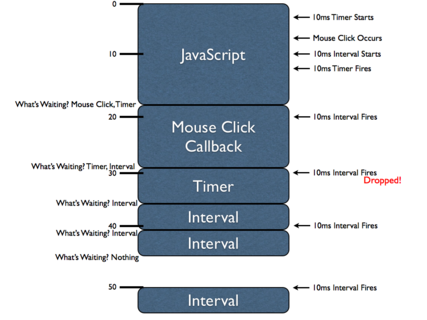

In order to understand how the timers work internally there’s one important concept that needs to be explored: timer delay is not guaranteed. Since all JavaScript in a browser executes on a single thread asynchronous events (such as mouse clicks and timers) are only run when there’s been an opening in the execution. This is best demonstrated with a diagram, like in the following:

(Click to view full size diagram)There’s a lot of information in this figure to digest but understanding it completely will give you a better realization of how asynchronous JavaScript execution works. This diagram is one dimensional: vertically we have the (wall clock) time, in milliseconds. The blue boxes represent portions of JavaScript being executed. For example the first block of JavaScript executes for approximately 18ms, the mouse click block for approximately 11ms, and so on.

Since JavaScript can only ever execute one piece of code at a time (due to its single-threaded nature) each of these blocks of code are “blocking” the progress of other asynchronous events. This means that when an asynchronous event occurs (like a mouse click, a timer firing, or an XMLHttpRequest completing) it gets queued up to be executed later (how this queueing actually occurs surely varies from browser-to-browser, so consider this to be a simplification).

To start with, within the first block of JavaScript, two timers are initiated: a 10mssetTimeout and a 10ms setInterval. Due to where and when the timer was started it actually fires before we actually complete the first block of code. Note, however, that it does not execute immediately (it is incapable of doing that, because of the threading). Instead that delayed function is queued in order to be executed at the next available moment.

Additionally, within this first JavaScript block we see a mouse click occur. The JavaScript callbacks associated with this asynchronous event (we never know when a user may perform an action, thus it’s consider to be asynchronous) are unable to be executed immediately thus, like the initial timer, it is queued to be executed later.

After the initial block of JavaScript finishes executing the browser immediately asks the question: What is waiting to be executed? In this case both a mouse click handler and a timer callback are waiting. The browser then picks one (the mouse click callback) and executes it immediately. The timer will wait until the next possible time, in order to execute.

Note that while mouse click handler is executing the first interval callback executes. As with the timer its handler is queued for later execution. However, note that when the interval is fired again (when the timer handler is executing) this time that handler execution is dropped. If you were to queue up all interval callbacks when a large block of code is executing the result would be a bunch of intervals executing with no delay between them, upon completion. Instead browsers tend to simply wait until no more interval handlers are queued (for the interval in question) before queuing more.

We can, in fact, see that this is the case when a third interval callback fires while the interval, itself, is executing. This shows us an important fact: Intervals don’t care about what is currently executing, they will queue indiscriminately, even if it means that the time between callbacks will be sacrificed.

Finally, after the second interval callback is finished executing, we can see that there’s nothing left for the JavaScript engine to execute. This means that the browser now waits for a new asynchronous event to occur. We get this at the 50ms mark when the interval fires again. This time, however, there is nothing blocking its execution, so it fires immediately.

Let’s take a look at an example to better illustrate the differences betweensetTimeout and setInterval.

setTimeout(function(){

/* Some long block of code... */

setTimeout(arguments.callee, 10);

}, 10);

setInterval(function(){

/* Some long block of code... */

}, 10);

These two pieces of code may appear to be functionally equivalent, at first glance, but they are not. Notably the setTimeout code will always have at least a 10ms delay after the previous callback execution (it may end up being more, but never less) whereas the setInterval will attempt to execute a callback every 10ms regardless of when the last callback was executed.

There’s a lot that we’ve learned here, let’s recap:

- JavaScript engines only have a single thread, forcing asynchronous events to queue waiting for execution.

setTimeout and setInterval are fundamentally different in how they execute asynchronous code.- If a timer is blocked from immediately executing it will be delayed until the next possible point of execution (which will be longer than the desired delay).

- Intervals may execute back-to-back with no delay if they take long enough to execute (longer than the specified delay).

All of this is incredibly important knowledge to build off of. Knowing how a JavaScript engine works, especially with the large number of asynchronous events that typically occur, makes for a great foundation when building an advanced piece of application code.

from: http://ejohn.org/blog/how-javascript-timers-work/